INTRODUCTION

Childs Frick (1883–1965), son of Pittsburgh industrialist Henry Clay Frick (1849–1919), led two expeditions to Africa. The first, in 1909–10, was to British East Africa where he collected 126 mammals for Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Few details of this trip have come to light in archival research. The second, in 1911–12, officially the Childs Frick Abyssinian Expedition, also included British East Africa. It is well documented in the scientific literature and various archives and is the main focus of this website. Accompanying Frick on the second expedition were Edgar A. Mearns (1856–1916), Dr. Donald G. Rafferty of Pittsburgh (1882–1930), friend Alfred Bradley, and field collector John C. Blick, who later became an associate of the Frick Laboratory at the American Museum of Natural History. Over 500 mammals were collected for the Carnegie Museum and some 5,000 birds were collected for the United States National Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. The accompanying story map shows the route that was taken by the second expedition as well as trip highlights.*

The Frick party arrived on the African continent after a sea voyage of three weeks then journeyed inland by rail, leaving from Djibouti on November 25, 1911. Traveling south through today’s Ethiopia and Kenya, the bulk of the route was by foot or pack animals. The expedition picked up the Uganda Railway in southern Kenya and continued to the east coast, where they sailed from the port of Mombasa on September 16, 1912.

Original exhibits in the Carnegie Museum of Natural History have been updated in recent years, but many of the mammals that Frick collected over a hundred years ago are on view in the museum’s Hall of African Wildlife. Prepared by chief taxidermist, Remi H. Santens, and his brother, Joseph A. Santens, the exhibits display animals in natural poses with vegetation from their native environment, a revolutionary concept when first displayed. The taxidermy team’s artistic talent and meticulous attention to detail resulted in a collection of extraordinarily lifelike African wildlife that still meets 21st-century exhibition standards.

* Place names shown are those that were in use at the time of the expedition. Modern names are in parentheses.

BIOGRAPHIES

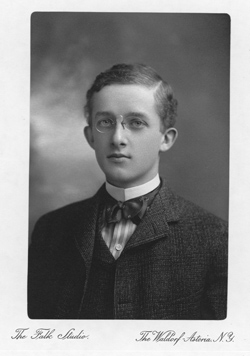

CHILDS FRICK (1883–1965)

_-_DSC05033_sm.jpg)

|

Born in Pittsburgh, Childs Frick was the first of four children of industrialist Henry Clay Frick and Adelaide Howard Childs. He spent his childhood at Clayton, the family estate in Pittsburgh, exhibiting an early interest in studying the rocks, plants, and animals in the surrounding wooded areas and experimenting with photography and taxidermy.

Frick attended Sterrett School and Shady Side Academy in Pittsburgh and graduated from Princeton University in 1905, the same year his father moved the family from Pittsburgh to New York City. Early hunting trips to Canada and the American West fueled Frick’s growing enthusiasm for adventure and led to his first trip to British East Africa (Kenya) in 1909–10, where he encountered the remarkable big game of Africa. Motivated by the success of the Smithsonian’s African Expedition, led by Theodore Roosevelt during that same time period, Frick planned a more ambitious safari that began in Abyssinia (Ethiopia) in 1911 and ended in British East Africa in 1912. He was gone nearly a year from the time he left New York by steamship until his return to the United States. The specimens collected on these two trips became the foundation of the African mammal collection at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

In 1913, Frick paused from traveling to marry Frances Shoemaker Dixon (1892–1953) in Baltimore. Shortly thereafter the couple returned to Pittsburgh so that he could manage the Frick family’s business affairs. It caused a strain in the relationship with his father, however, since Childs was more interested in the natural sciences than in business. During World War I Frick was sent to California to serve in the U.S. Army’s Signal Corps, accompanied by his wife and two young children. There he studied the geological and paleontological history of the Pacific Coast through a University of California program. By this time his primary focus had turned to fossil mammals, and he was more interested in wilderness and wildlife preservation than in collecting big game.

|

After the war Frick and his family returned to the East Coast where his scientific career continued. His father was so delighted at their return that he purchased a mansion for the couple in Roslyn, Long Island, twenty miles east of New York City. They named it Clayton, after Frick’s boyhood home, and raised four children there: Adelaide, Frances, Martha, and Henry Clay II (“Clay”). There was plenty of space for Frick to indulge his love of sports, and the grounds eventually included tennis courts, a polo field, swimming pool and ponds, a private zoo, and even a ski slope with its own snowmaking machine. He and his wife shared a passion for horticulture and worked with renowned landscape architect Marion Cruger Coffin to create the formal French gardens.

It was while living at Clayton that Frick began his association with the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), becoming a long–time trustee and benefactor and establishing the Frick Laboratory of Vertebrate Paleontology. His field trips contributed over 200,000 fossil specimens to the museum and are now housed in the Childs Frick Building, completed in 1973.

Frick maintained close ties to Carnegie Museum and was named Honorary Curator of Mammals in 1920, in recognition of his interest in the work of the museum and his contributions to the collections. He visited Pittsburgh frequently and kept up an active correspondence with museum director Andrey Avinoff, who also had a home on Long Island. He made regular financial gifts to the museum, and the Paleontology Department especially benefited from his support of fossil–hunting trips that otherwise wouldn’t have been possible. Loans from the museum’s collection of fossil and Recent mammals were frequently sent to him to study at AMNH or at Millstone, his personal research laboratory at Clayton, and he authored numerous publications on his findings.

|

Frick would later come to own property in Bermuda, called “Castle Point,” where his love of nature was demonstrated in his conservation efforts. He worked with the Bermuda Agricultural Station in experimenting with different types of vegetation that could withstand the island’s salt spray and took a lead role in the preservation of bird life, especially the cahow, or Bermuda petrel, a nocturnal seabird on the brink of extinction.

In addition to his recognition as a respected paleontologist, Frick accumulated a long list of honorifics and was associated with numerous societies and clubs dedicated to natural history and conservation. Four years after his death at the age of 82, Nassau County purchased the Clayton estate, where he lived for almost fifty years, and established the Nassau County Museum of Art. Frick is buried in the family plot in Pittsburgh's Homewood Cemetery.

EDGAR ALEXANDER MEARNS (1856–1916)

|

Edgar A. Mearns, army surgeon and naturalist, was born in Highland Falls, near West Point, New York, to Alexander and Nancy Reliance (Carswell) Mearns. He developed an interest in birds and animals at an early age, learning their names and behaviors, and spending hours in the woods. When he was about ten years old he began to document his observations on birds and, as a teenager, accumulated a collection of carefully labelled flora and fauna specimens.

Mearns’ interest in biology led to medical courses at the College of Physicians and Surgeons of New York (later to merge with Columbia University). While still in college he published his first scientific paper, “The Capture of several Rare Birds near West Point, N.Y.,” and met other young naturalists of the newly formed Linnaean Society of New York. After graduating in 1881, Mearns married Ellie Wittich who shared his interests in natural history and assisted in his collection work. They had two children, Louis di Zerega Mearns and Lillian Hathaway Mearns.

In 1882 Mearns joined the U.S. Army’s medical department, and served as a temporary curator of Ornithology at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) while awaiting his first military assignment. He later received his commission as assistant surgeon at Fort Verde, Arizona. His spare time was spent exploring ancient ruins and the unfamiliar plants and animals of the desert. Twenty–six years of active military service sent him to additional posts in Texas, New Mexico, California, Virginia, Rhode Island, Yellowstone National Park, and the Philippines, among others, collecting wherever he went and writing papers about his discoveries.

|

Mearns’ first association with the Smithsonian Institution, also known as the United States National Museum (USNM), was in 1892 when he was charged by the army to conduct a biological survey along the U.S.–Mexican border. He and his party spent two years collecting 30,000 plant and animal specimens that were presented to the museum. Upon completion of the survey he reported to Fort Meyer, Virginia, which allowed him to gather data and study the specimens at the nearby USNM. Mearns planned to publish a detailed multi–part report on his findings, but due to lack of funding from Congress only the first part on mammals was published.

Duty sent Mearns to the Philippines in 1903–04, where he not only served as a military surgeon but was instrumental in the formation of the Philippine Scientific Association. He obtained general biological collections as well as ethnographic material. Exhausting work and complications of tropical parasitic disorders caused him to be hospitalized at the end of the excursion. While still in recovery, he published five papers describing new mammals and birds from the Philippines. In 1905 Mearns returned to the Philippines for a two–year period and was placed in command of a “Biological and Geographical Reconnaissance of the Malindang Mountain Group,” in western Mindanao, which was organized to explore and map the region and collect its natural products.

Mearns’ next great adventure was with the Smithsonian–Roosevelt African Expedition. The Smithsonian recommended Mearns as a field naturalist and collector, and shortly after Theodore Roosevelt left presidential office the party sailed for Africa on March 23, 1909. While Roosevelt concentrated on big game, Mearns collected birds, small mammals, and plants. Of the 4,000 birds obtained, Mearns himself was responsible for over 3,000 of them. The expedition returned to the U.S. in 1910, and while Mearns was still studying his finds in Washington he was asked by Childs Frick to accompany him on another exploration of Africa. The opportunity to add to his research material was hard to resist and once again Mearns left New York City, in 1911, and returned almost a year later. This time over 5,000 birds, nests, and eggs were accumulated.

|

Having retired from active service in 1909 with the rank of Lieutenant–Colonel, Mearns at last had time to research and write about his collections. Poor health interrupted his studies, however. Tropical diseases, grueling collecting trips, and the complications of diabetes took their toll, reducing his productive work time more and more. Mearns died at the age of 60 at Walter Reed Army General Hospital leaving behind a wealth of research material. He was in the midst of preparing a comprehensive report on the birds collected in Africa, and masses of his notes from the Philippines were still unpublished. During his lifetime he authored well over a hundred scientific papers, and ultimately over fifty new taxa were named in his honor.

ON SAFARI

|

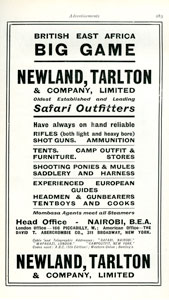

A trip to Africa in the early part of the 20th century was not one to be undertaken lightly (or cheaply). Months of planning went into organizing the logistics of how to get there, what to take, and what to do upon arrival. Safari outfitters, such as Newland, Tarlton & Company and Boma Trading Co., with offices in both London and Nairobi, helped make the job easier by supplying almost everything a hunter or naturalist needed in the way of camp equipment and food supplies. They could also arrange to hire porters, guides, armed security guards (askaris), gun-bearers, cooks, and “tent boys,” as well as a “headman” to supervise them all.

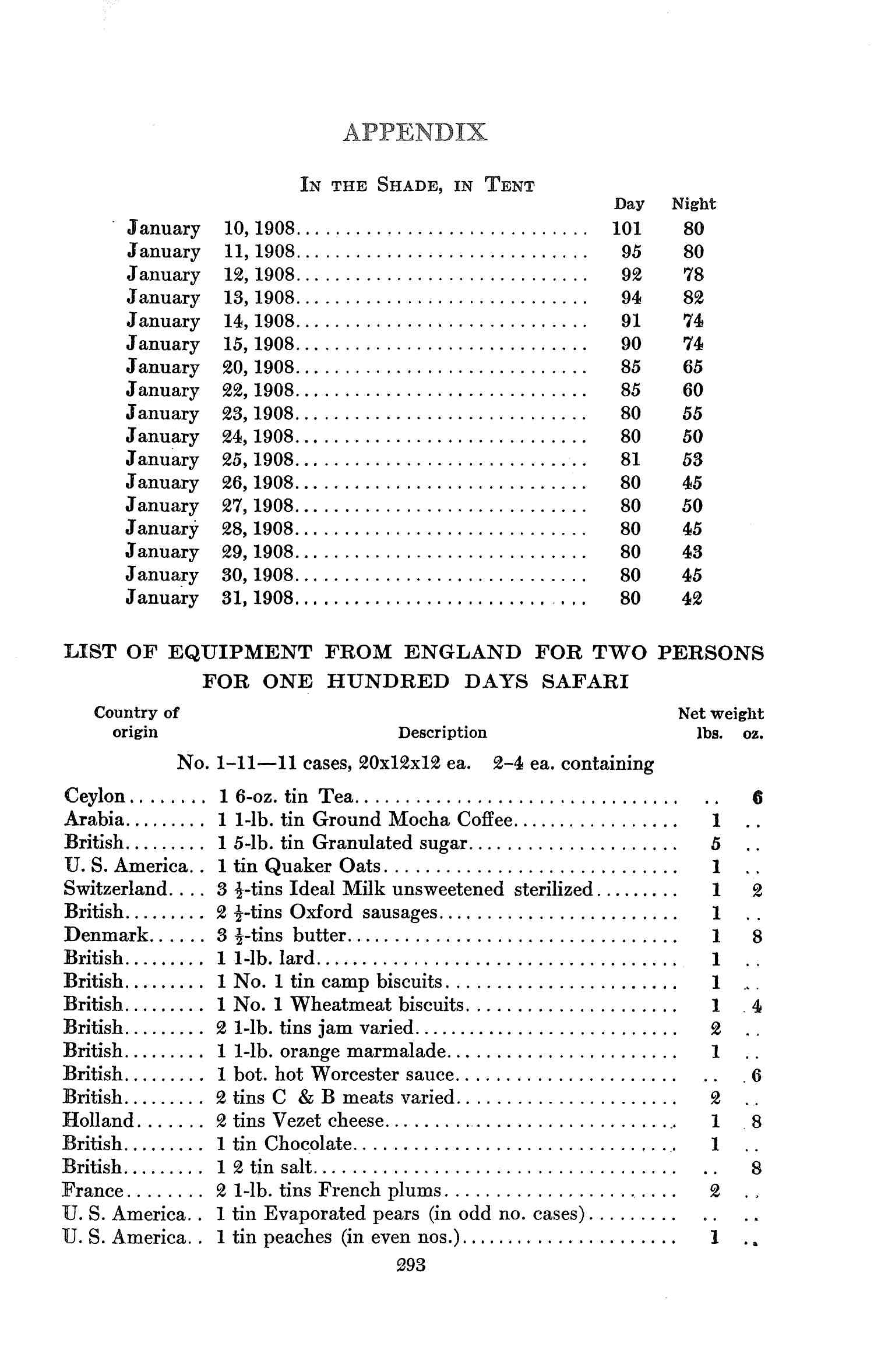

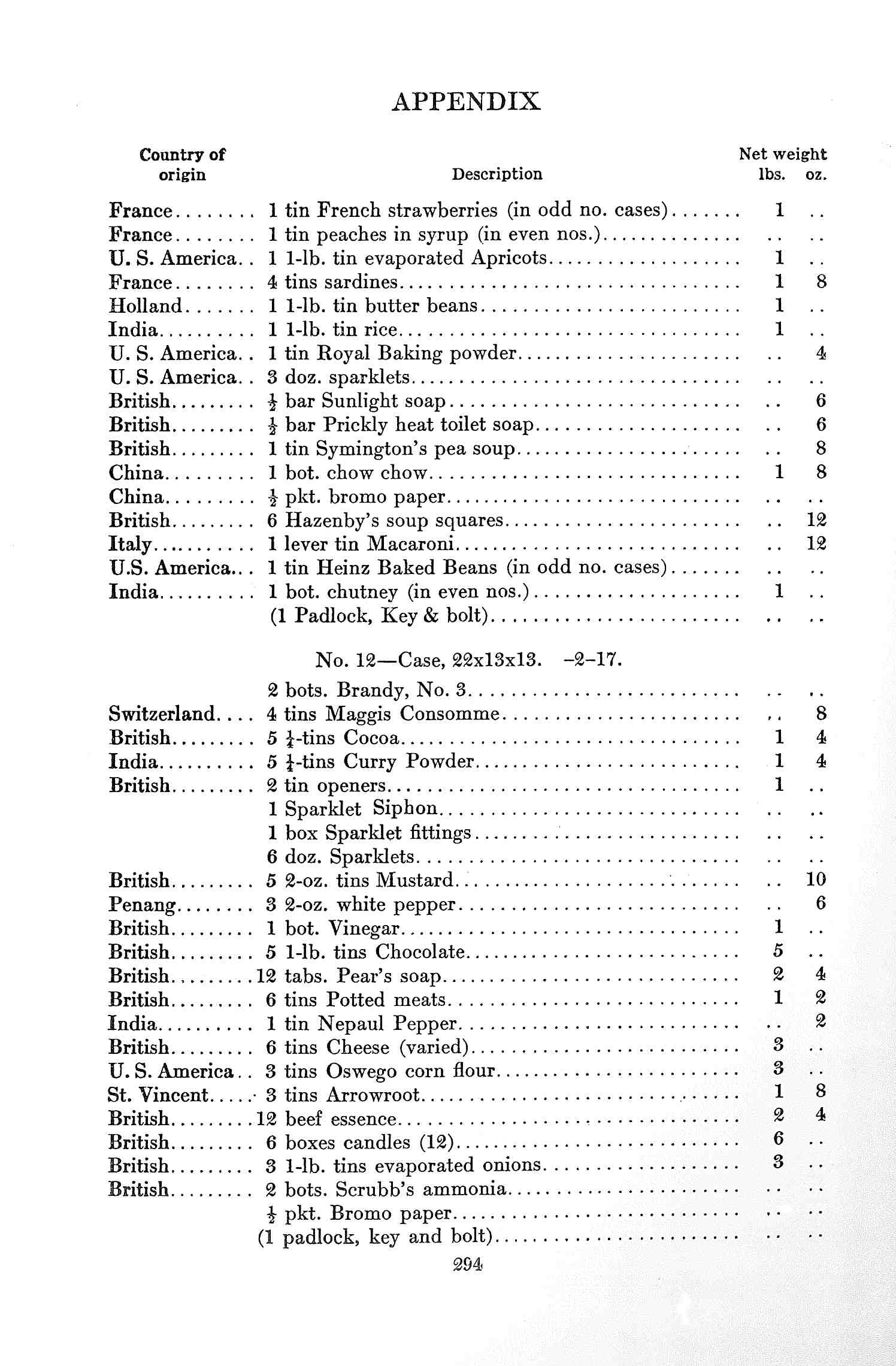

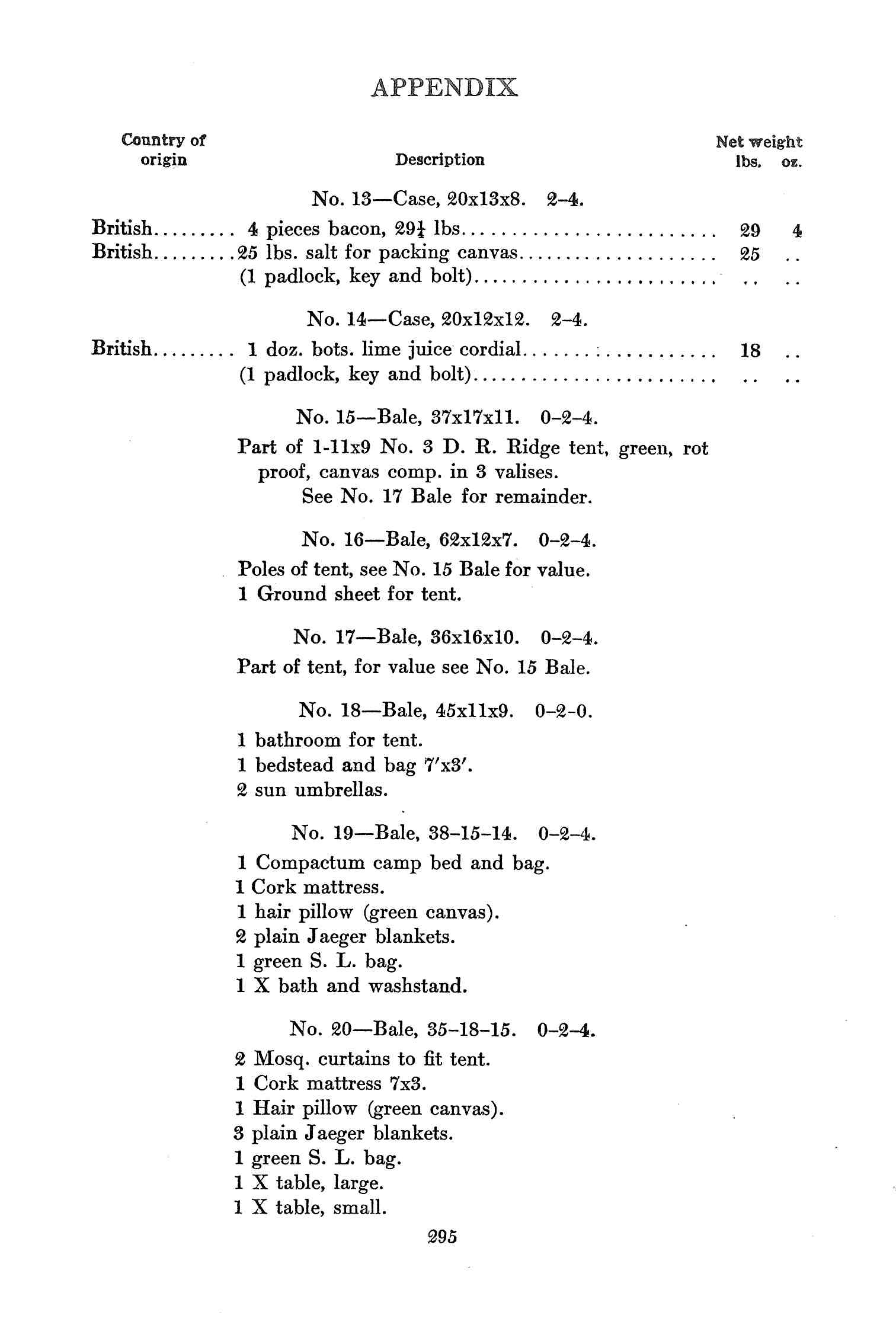

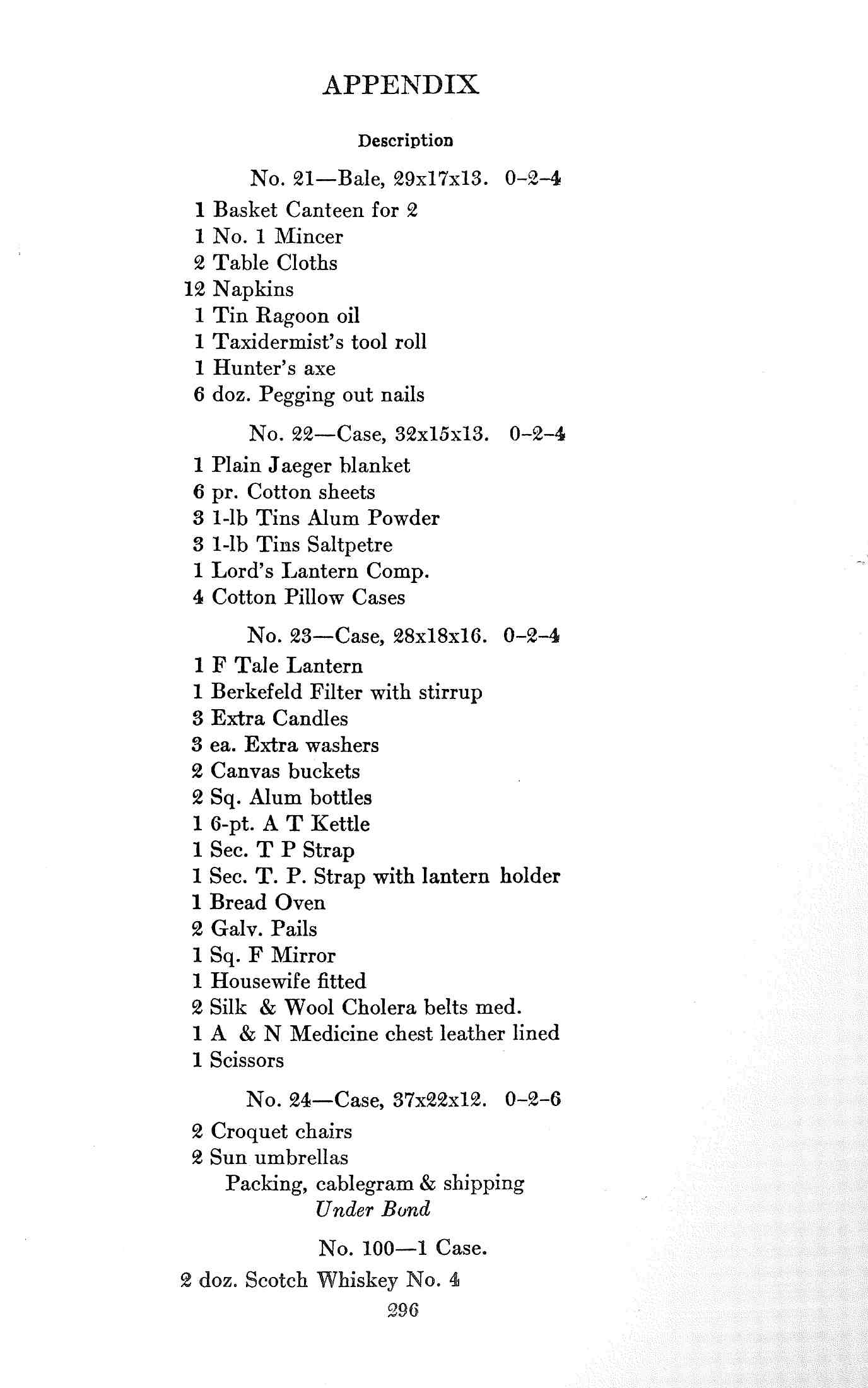

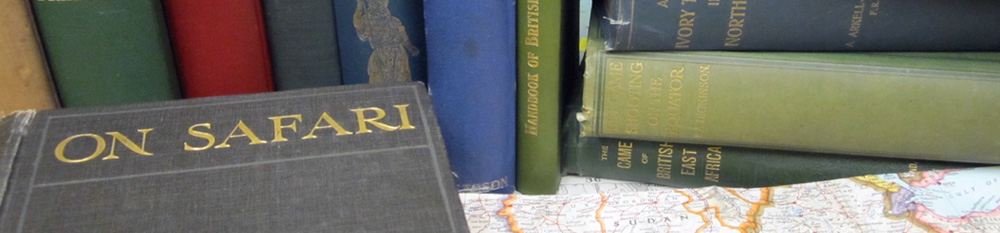

Frick's personal library included a large collection of books about Africa and the adventurers who journeyed there, and many of them offered advice on travel itineraries and equipment lists. Percy C. Madeira's Hunting in British East Africa (1909) included a “List of equipment from England for two persons for one hundred days safari.” In addition to basic camping supplies and food, Madeira's essentials included chocolate, brandy, and Scotch whiskey.

|

The costs of going on safari meant it was largely a pursuit of the privileged classes. In The Land of the Lion (1909), W. S. Rainsford's estimate was $500 a month for an expedition of three to four months for two people and about 60 porters, but not including food for the sportsmen, guns and ammunition, hunting licenses, customs fees, and railroad travel. This translates to well over $10,000 a month in today's money. Additional costs could be incurred for longer trips into more remote areas, not to mention the expenses of preparing, packing, and shipping trophies home.

A typical day on safari meant breakfast by candlelight, heading out before dawn, and reaching the next camp by mid-day in order to avoid the strong afternoon sun. The distance covered varied considerably, depending on the terrain. A twenty-mile hike would be considered a pretty good day, but twelve to fifteen miles was probably more common. The porters, most carrying 60-pound loads, were skilled in quickly setting up camp, and each had a specific duty to attend to whether it was tent-pitching, unloading provisions, or gathering firewood and water.

|

If an army is said to “march on its stomach,” it might be equally true for a safari. The contentment of the crew and their ability to function efficiently could well depend on the availability of fresh meat. Fresh fruits and vegetables were scarce, but game of some kind could usually be found to supplement the tinned and dried staples and the porters' daily “posho” (usually grain of some kind and possibly rice and/or beans). Game meat was often tough and stringy, and sometimes hours of boiling failed to make it palatable. The natives, with decidedly different tastes than the Europeans or Americans, were said to be fond of zebra and elephant flesh, usually raw or barely cooked. Rhino-tongue soup, ostrich-egg omelets, wildebeest liver and bacon, and giraffe marrow might be on the menu for the safari clients. A dinner example from Abel Chapman's book, On Safari (1908), included: marrow-soup, cutlets of gazelle, spatchcocked guinea-fowl, curried venison, and marvelous pudding (cornflour from Glasgow, peaches from Australia, or pineapple from Natal), with tea and a final “tot.”

|

Once a hunter collected his trophies, it was essential to treat the skins and skulls properly before shipping them home. Insects, rot, and unpredictable weather could quickly cause a prized specimen to become unusable for a taxidermy mount. Drying and preservative agents commonly used in the field included wood ash, alum, arsenic, turpentine, and napthalene (found in mothballs). For those who managed to bag an elephant it was especially challenging to transform such a large animal into a transportable package. In Vivienne de Watteville's, Out in the Blue (1927), it took a dozen boys standing on a folded elephant skin, pulling it taut with ropes, to reduce it to a 5 x 6 x 2 ft. cube. The extraordinary weight of the skin required five men to carry it.

|

Frick donated many of the African specimens he collected to the museum and played an active role in how they would be mounted and displayed by providing dimensions, drawings, and ideas to the preparators and taxidermy artists. With their innovative techniques and attention to detail, chief taxidermist Remi Santens and his brother, Joseph, were renowned for creating lifelike mounts, and their work can still be seen today in the museum's Hall of African Wildlife.

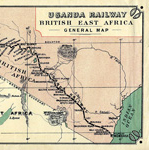

UGANDA RAILWAY

|

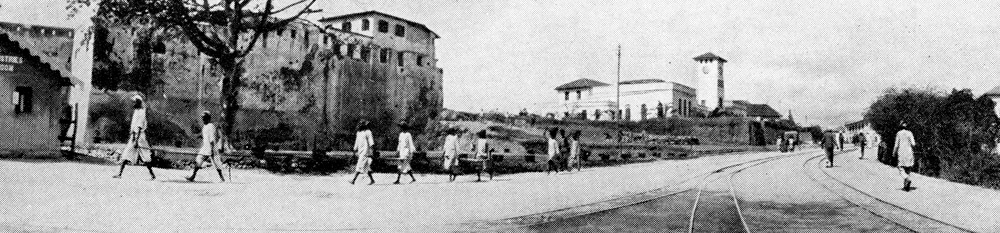

Built by the British government, and named for its ultimate destination, the Uganda Railway didn’t actually reach Uganda. Construction began in 1896 in the port city of Mombasa and continued its course northwest through today’s Kenya to its terminus on the eastern shore of Lake Victoria. Progress came at a high cost, however, not just financially but in the thousands of workers who lost their lives. Complicated by political resistance, difficult terrain, disease, warring tribes, and man-eating lions, the line finally reached Lake Victoria in 1901. Travelers wanting to continue on to Uganda would then take a steamship across the lake to Entebbe, Uganda’s former capital.

|

Such a remarkable feat of engineering required an enormous number of workers, and some 32,000 laborers were imported from British India. Once the railway was completed many of them stayed in the region to take advantage of new opportunities, forming the nucleus of what would become a sizable South Asian community of merchants, businessmen, and administrators.

This strategic link between Britain’s East Africa and Uganda Protectorates allowed goods and raw materials to flow between the east coast of Africa and its landlocked interior. Easier access encouraged European settlement and farming, and the railway contributed greatly to the popularity of the safari business by easily transporting supplies and equipment that would have taken an army of porters, each carrying 60 to 80-pound loads, some four and a half months to walk the length of the line from one end to the other. The transformation of a mostly-inaccessible territory prompted the South African Railway Magazine to declare that “the Uganda Railway has literally created a new country.”

|

After leaving Mombasa, the train eventually climbed to over 8,000 feet above sea level, traveling through hills, valleys, and plains; forest, swamp, and desert; and every climate from steamy tropical heat to near-freezing temperatures. From coast to lake, a journey of almost two days, there was plenty of time to marvel at the passing scenery and wildlife from the comfort of the passenger coach. After the first hundred miles or so game was common and could be seen on all sides. The traveler was likely to see zebras, ostriches, hartebeest, wildebeest, and gazelles grazing near the train tracks. Further on, where the line crossed the Athi Plains near Nairobi, huge herds of these animals roamed as far as the eye could see across the open country. Giraffe, elephants, and rhinos were occasionally spotted, and lions were said to plentiful near Simba station.

|

Some of the best hunting was in the Nairobi area, and the railway provided an easy way in and out for those who didn’t want to stray too far off the beaten path. The town became the center of the safari industry, as well as the headquarters of the Uganda Railway, eventually developing into the capital and largest city of Kenya. The railway brought economic opportunities, population growth, and urbanization to many of the interior towns along the line, and what were once merely stopping points or small depots are today some of Kenya’s largest cities.

GAZETTEER

MAMMALS LIST

Artiodactyla: Bovidae

| Aepyceros melampus suara— | CM 2013, CM 2114 |

| Alcelaphus buselaphus— | CM 2007, CM 2008, CM 2026, CM 2075, CM 2084, CM 2089, CM 5808, CM 5809, CM 5820, CM 5840, CM 5843, CM 5874, CM 20873, CM 20874 |

| Antidorcas marsupialis— | CM 5818 |

| Capra walie— | CM 5879, CM 5880, CM 5881 |

| Capra sp.— | CM 20900 |

| Cephalophus sp.— | CM 2097, CM 20875, CM 20876, CM 20877, CM 20878 |

| Connochaetes taurinus— | CM 2012, CM 2115, CM 2121, CM 2122 |

| Damaliscus korrigum— | CM 2080, CM 2082 |

| Eudorcas thomsonii— | CM 2011, CM 2014, CM 2015 |

| Gazella dorcas— | CM 5882, CM 20889 |

| Gazella sp.— | CM 20890 |

| Hippotragus equinus— | CM 2085, CM 2086 |

| Kobus ellipsiprymnus— | CM 2010, CM 2017, CM 2020, CM 2091, CM 2092, CM 2094, CM 20885 |

| Litocranius walleri— | CM 2040, CM 2041, CM 2046, CM 2052, CM 2053, CM 2054, CM 2056, CM 2058, CM 2059, CM 2063, CM 20891 |

| Madoqua guentheri— | CM 5815, CM 5816, CM 5817, CM 5825 |

| Madoqua sp.— | CM 2024, CM 2027, CM 2029, CM 2030, CM 2031, CM 2049, CM 2050, CM 2051, CM 2062, CM 2064, CM 2065, CM 2102, CM 2104, CM 5769, CM 5772, CM 5780, CM 5826, CM 5827, CM 5835, CM 5836, CM 5837, CM 5841, CM 5842, CM 5848, CM 5849, CM 5884, CM 20880, CM 20881, CM 20882, CM 20883, CM 20884 |

| Nanger granti— | CM 2035, CM 2036, CM 2045, CM 2116, CM 2117, CM 2118, CM 5819, CM 5851, CM 5876, CM 5878, CM 5890, CM 20887, CM 20888 |

| Nanger soemmeringi— | CM 5776, CM 5777, CM 5778 |

| Oreotragus oreotragus— | CM 2039, CM 2068, CM 2069, CM 2070, CM 2072, CM 5838 |

| Oryx beisa annectens— | CM 2016, CM 2037, CM 2066, CM 2123, CM 5832, CM 20892, CM 20893, CM 20894 |

| Ourebia ourebia— | CM 2078, CM 2083, CM 5784, CM 5785, CM 5786, CM 5791, CM 5812, CM 5813, CM 5814 |

| Raphicerus campestris— | CM 2076, CM 2113 |

| Raphicerus sp.— | CM 20879 |

| Redunca fulvorufula— | CM 2006, CM 2018 |

| Redunca redunca— | CM 2087, CM 2090, CM 2093, CM 5792, CM 5796, CM 5801, CM 5821, CM 5822, CM 5823, CM 5830, CM 5839, CM 20886 |

| Redunca sp.— | CM 5824 |

| Sylvicapra grimmia— | CM 2025, CM 2028, CM 2032, CM 2079, CM 2088, CM 2096, CM 2101, CM 2108, CM 5782, CM 5783, CM 5793 |

| Syncerus caffer— | CM 2021, CM 2023, CM 20901 |

| Taurotragus oryx— | CM 2067, CM 5877, CM 20897 |

| Tragelaphus buxtoni— | CM 5787, CM 5788, CM 5789, CM 5795, CM 5797, CM 5798, CM 5799, CM 5802 |

| Tragelaphus imberbis— | CM 2105, CM 2106, CM 2107, CM 2109, CM 5779, CM 5859 |

| Tragelaphus scriptus— | CM 2019, CM 2022, CM 2034, CM 5770, CM 5771, CM 5790, CM 5794 |

| Tragelaphus strepsiceros— | CM 5831, CM 5833 |

| Tragelaphus sp.— | CM 20895, CM 20896, CM 20898, CM 20899 |

Artiodactyla: Giraffidae

| Giraffa camelopardalis— | CM 2071, CM 2112, CM 5834 |

Artiodactyla: Hippopotamidae

| Hippopotamus amphibius— | CM 2033 |

Artiodactyla: Suidae

| Phacochoerus africanus— | CM 2098, CM 2099, CM 2100, CM 5850, CM 5864, CM 5870 |

Carnivora: Canidae

| Canis aureus— | CM 5781, CM 5854, CM 5886 |

| Canis mesomelas— | CM 2043, CM 2047, CM 2048, CM 2119, CM 5773, CM 5855, CM 5856, CM 5889, CM 20868, CM 20869, CM 20870 |

| Canis simensis citernii— | CM 5800, CM 5803 |

| Lycaon pictus— | CM 5869 |

| Otocyon megalotis— | CM 5860, CM 5861, CM 5863, CM 5894, CM 20867 |

Carnivora: Felidae

| Acinonyx jubatus— | CM 2077 |

| Felis silvestris— | CM 5853, CM 5885, CM 20872 |

| Panthera leo— | CM 5868 |

| Panthera pardus— | CM 2057, CM 5867 |

Carnivora: Herpestidae

| Helogale parvula— | CM 4390, CM 4401 |

Carnivora: Hyaenidae

| Crocuta crocuta— | CM 2073, CM 2081, CM 5862, CM 5866, CM 5873, CM 20871 |

| Hyaena hyaena— | CM 2042, CM 2044, CM 5857, CM 5865 |

Carnivora: Mustelidae

| Mellivora capensis— | CM 5852, CM 5875 |

Carnivora: Viverridae

| Genetta genetta— | CM 5774, CM 5775 |

Chiroptera: Hipposideridae

| Hipposideros caffer— | CM 3448, CM 4379, CM 4382, CM 4383 |

Chiroptera: Megadermatidae

| Cardioderma cor— | CM 4403 |

| Lavia frons— | CM 4391, CM 4399, CM 4402, CM 4404, CM 4405, CM 4406, CM 4409, CM 4410, CM 4415, CM 4416, CM 4417, CM 4419, CM 4421, CM 4422 |

Chiroptera: Pteropodidae

| Epomophorus labiatus— | CM 4414 |

Hyracoidea: Procaviidae

| Procavia capensis— | CM 4392, CM 4393, CM 4394, CM 4395, CM 4396, CM 4397, CM 4398, CM 4400, CM 4411, CM 4412 |

Erinaceomorpha: Erinaceidae

| Atelerix albiventris— | CM 4423 |

Soricomorpha: Soricidae

| Crocidura fuscomurina— | CM 4413 |

| Crocidura glassi— | CM 4384 |

| Crocidura olivieri— | CM 4385 |

| Crocidura sp.— | CM 4418 |

Lagomorpha: Leporidae

| Lepus capensis— | CM 3507, CM 3517, CM 3518, CM 3554, CM 3555, CM 3556, CM 3568, CM 3570, CM 3571, CM 3582, CM 3583 |

| Lepus habessinicus— | CM 3520, CM 3521, CM 3530, CM 3533, CM 3581 |

Macroscelidea: Macroscelididae

| Elephantulus rufescens— | CM 4380, CM 4386, CM 4387, CM 4388, CM 4389 |

Perissodactyla: Equidae

| Equus grevyi— | CM 2060, CM 5858 |

| Equus quagga— | CM 2009, CM 2038, CM 2061, CM 2120 |

Perissodactyla: Rhinocerotidae

| Diceros bicornis— | CM 2074 |

Primates: Cercopithecidae

| Chlorocebus aethiops— | CM 5844, CM 5845, CM 5846, CM 5871, CM 5872, CM 20860 |

| Chlorocebus pygerythrus— | CM 20854, CM 20855, CM 20861 |

| Cercopithecus albogularis— | CM 5887, CM 5888, CM 20856, CM 20857, CM 20858, CM 20859, CM 20862 |

| Cercopithecus sp.— | CM 20863, CM 20864 |

| Colobus guereza— | CM 5804, CM 5805, CM 5806, CM 58078, CM 5810, CM 5811, CM 20866 |

| Papio anubis doguera— | CM 2055, CM 2095, CM 5828, CM 5829 |

| Papio cynocephalus— | CM 2103 |

| Papio hamadryas— | CM 5765, CM 5766, CM 5767, CM 5768, CM 20865 |

Primates: Lorisidae

| Galago senegalensis— | CM 4407, CM 4408 |

Proboscidea: Elephantidae

| Loxodonta africana— | CM 2124 |

Rodentia: Cricetidae

| Gerbillus pulvinatus— | CM 3491, CM 3492, CM 3511 |

| Gerbillus pusillus— | CM 3559, CM 3578 |

| Gerbilliscus nigricaudus— | CM 3543, CM 3579 |

| Gerbilliscus robustus— | CM 3440, CM 3534, CM 3535, CM 3537, CM 3547 |

Rodentia: Muridae

| Acomys cineraceus— | CM 3497 |

| Acomys louisae— | CM 3490, CM 3494, CM 3495, CM 3496, CM 3536, CM 3561 |

| Acomys percivali— | CM 3439, CM 3467, CM 3470, CM 3471, CM 3472, CM 3473, CM 3474, CM 3475, CM 3476, CM 3478, CM 3479, CM 3481, CM 3485, CM 3487, CM 3493, CM 3528, CM 3529, CM 3545, CM 3546 |

| Acomys sp.— | CM 3484 |

| Aethomys hindei— | CM 3468, CM 3469, CM 3482 |

| Arvicanthis blicki— | CM 3418, CM 3419, CM 3420, CM 3421, CM 3422, CM 3423, CM 3424, CM 3425, CM 3426, CM 3427, CM 3430, CM 3432, CM 3522, CM 3523, CM 3524 |

| Arvicanthis neumanni— | CM 3573 |

| Arvicanthis niloticus— | CM 3442, CM 3443, CM 3444, CM 3445, CM 3445, CM 3446, CM 3449, CM 3450, CM 3451, CM 3452, CM 3453, CM 3454, CM 3455, CM 3457, CM 3458, CM 3459, CM 3460, CM 3461, CM 3462, CM 3463, CM 3464, CM 3465, CM 3466, CM 3488, CM 3514, CM 3515, CM 3516, CM 3527, CM 3580 |

| Desmomys harringtoni— | CM 3437 |

| Lophuromys flavopunctatus— | CM 3431, CM 3434, CM 3438 |

| Mastomys erythroleucus— | CM 3417, CM 3436 |

| Mastomys natalensis— | CM 3441, CM 3447, CM 3456, CM 3477, CM 3480, CM 3483, CM 3486, CM 3489, CM 3498, CM 3512, CM 3544 |

| Mus musculoides— | CM 3560 |

| Otomys typus— | CM 3433, CM 3519 |

| Stenocephalemys albipes— | CM 3435, CM 3513 |

| Stenocephalemys albocaudata— | CM 3415, CM 3416, CM 3428, CM 3429 |

Rodentia: Rhizomyidae

| Tachyoryctes spalacinus— | CM 3574 |

| Tachyoryctes splendens— | CM 3532, CM 4420 |

Rodentia: Sciuridae

| Heliosciurus rufobrachium— | CM 3525 |

| Paraxerus ochraceus— | CM 3562, CM 3564, CM 3565, CM 3566, CM 3572, CM 3576, CM 3577 |

| Xerus erythropus leucoumbrinus— | CM 3526, CM 3531, CM 3575 |

| Xerus rutilus— | CM 3499, CM 3500, CM 3501, CM 3502, CM 3503, CM 3504, CM 3505, CM 3506, CM 3508, CM 3509, CM 3510, CM 3538, CM 3539, CM 3540, CM 3541, CM 3542, CM 3548, CM 3549, CM 3550, CM 3551, CM 3552, CM 3553, CM 3557, CM 3558, CM 3563, CM 3567, CM 3569 |

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alden, Peter C., Richard D. Estes, Duane Schlitter, and Bunny McBride. National Audubon Society Field Guide to African Wildlife. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1995.

Arkell-Hardwick, A. An Ivory Trader in North Kenia: The Record of an Expedition Through Kikuyu to Galla-Land in East Equatorial Africa. London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1903.

Bland-Sutton, J. Man and Beast in Eastern Ethiopia: From Observations Made in British East Africa, Uganda, and the Sudan. London: MacMillan and Co., 1911.

Buxton, Edward North. Two African Trips, with Notes and Suggestions on Big Game preservation in Africa. London: Edward Stanford, 1902.

Chapman, Abel. On Safari: Big-Game Hunting in British East Africa, with Studies in Bird-Life. London: Edward Arnold, 1908.

Dickinson, F. A. Big Game Shooting on the Equator. London and New York: John Lane, 1908.

Dugmore, A. Radclyffe. Camera Adventures in the African Wilds. New York: Doubleday, Page & Co., 1910.

Herne, Brian. White Hunters: The Golden Age of African Safaris. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1999.

Frick, Childs. “A New Genus and Some New Species and Subspecies of Abyssinian Rodents.” Annals of the Carnegie Museum 9, nos. 1-2 (1914).

Friedmann, Herbert. Birds Collected by the Childs Frick Expedition to Ethiopia and Kenya Colony: Part 1. Non-Passeres. Bulletin 153. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, United States National Museum, 1930.

—. Birds Collected by the Childs Frick Expedition to Ethiopia and Kenya Colony: Part 2. Passeres. Bulletin 153. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, United States National Museum, 1937.

Gangewere, R. Jay. “The Hall of African Wildlife.” Carnegie Magazine, May/June 1993.

Hindlip, Lord. Sport and Travel: Abyssinia and British East Africa. London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1906.

Jessen, B. H. W. N. McMillan’s Expeditions and Big Game Hunting in Southern Sudan, Abyssinia & East Africa. London: Marchant Singer & Co., 1906.

Keane, A. H. Stanford’s Compendium of Geography and Travel: Africa. Vol. 1, North Africa. 2d ed., rev. London: Edward Stanford, 1907.

—. Stanford’s Compendium of Geography and Travel: Africa. Vol. 2, South Africa. 2d ed., rev. and corr. London: Edward Stanford, 1904.

Landor, A. Henry Savage. Across Widest Africa: An Account of the Country and Its People of Eastern, Central and Western Africa as Seen During a Twelve Months’ Journey from Djibuti to Cape Verde. Vol. 1. London: Hurst and Blackett Ltd., 1907.

MacQueen, Peter. In Wildest Africa: The Record of a hunting and exploration trip through Uganda, Victoria Nyanza, the Kilimanjaro Region and British East Africa…. Boston: L. C. Page & Co., 1909.

Madeira, Percy C. Hunting in British East Africa. Philadelphia and London: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1909.

Powell-Cotton, P. H. G. A Sporting Trip through Abyssinia. London: Rowland Ward, 1902.

Rainsford, W. S. The Land of the Lion. New York: Doubleday, Page & Co., 1909.

Roosevelt, Theodore. African Game Trails: An Account of the African Wanderings of an American Hunter-Naturalist. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1910.

Sanger, Martha Frick Symington. Henry Clay Frick: An Intimate Portrait. New York, London, Paris: Abbeville Press, 1998.

—. The Henry Clay Frick Houses: Architecture, Interior, Landscapes in the Golden Era. New York: The Monacelli Press, Inc., 2001.

Schlitter, Duane, and Janis Sacco. “Childs Frick and the Santens Brothers: Creating a Superb Collection of African Mammals.” Carnegie Magazine, May/June 1993.

Smith, A. Donaldson. Through Unknown African Countries: The First Expedition from Somaliland to Lake Lamu. London and New York: Edward Arnold, 1897.

Smithsonian Institution. Expeditions Organized or Participated In by the Smithsonian Institution in 1910 and 1911. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, vol. 59, no. 11. Washington, D.C., 1912.

—. Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution…for the year ending June 30, 1917. Washington, D.C., 1919.

The Standard Printing & Publishing Works, comps. The Red Book: The Directory of East Africa, Uganda & Zanzibar. Nairobi and Mombasa, 1912.

Stigand, C. H. The Game of British East Africa. London: Horace Cox, Windsor House, 1909.

Vivian, Herbert. Abyssinia: Through the Lion-Land, to the Court of the Lion of Judah. London: C. Arthur Pearson Ltd., 1901.

Ward, H. F., and J. W. Milligan. Handbook of British East Africa. Nairobi: The Caston (B.E.A.) Printing & Publishing Co., Ltd., 1912.

de Watteville, Vivienne. Out in the Blue. London: Methuen & Co. Ltd., 1927.

Wellby, M. S. ’Twixt Sirdar & Menelik: An Account of a Year’s Expedition from Zeila to Cairo through Unknown Abyssinia. London and New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1901.

White, Stewart Edward. The Rediscovered Country. Garden City and New York: Doubleday, Page & Co., 1915.

Wilson, Don E., and DeeAnn M. Reeder. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference. 3rd ed. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Grant support from the Institute of Museum and Library Services, grant #MA-05-12-0057-12

Contributing Carnegie Museum of Natural History staff:

Joel Marchewka, Suzanne B. McLaren, Lisa Miriello, Lisa J. Sisco,* Jacob Slyder, James V. Whitacre,** John R. Wible

*former staff

**currently University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

We would like to thank the following:

American Society of Mammalogists, Mammal Image Library

The Frick Collection and Frick Art Reference Library, New York

Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D. C.

IMAGE CREDITS

Hall of African Wildlife, Carnegie Museum of Natural History

Photo: Mindy McNaugher

Edgar A. Mearns (L) and unidentified member of Frick expedition, c. 1911–12

Ruthven Deane Collection, Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-115848

Souvenir postcard, Place Menelik, Djibouti, c. 1905

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Djibouti-c1905.jpg

Hipposideros caffer (Sundevall's Leaf-nosed Bat)

American Society of Mammalogists, Mammal Image Library

Photo: P. Laycock

Mearns (far L) and Frick (center) at campsite, c. 1911–12

Ruthven Deane Collection, Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-115844

Emperor Menelik II

From A. Henry Savage Landor, Across Widest Africa: An Account of the Country and Its People of Eastern, Central and Western Africa as Seen During a Twelve Months’ Journey from Djibuti to Cape Verde, Vol. I (London: Hurst and Blackett Ltd., 1907).

Holotype, Epimys rufidorsalis ankoberensis (Ethiopian white-footed narrow-headed rat)

Carnegie Museum of Natural History, CM 3513

Photo: John R. Wible

Iron bridge over Hawash River

From M. S. Wellby, ‘Twixt Sirdar & Menelik: An Account of a Year’s Expedition from Zeila to Cairo through Unknown Abyssinia (Harper & Brothers Publishers, London and New York, 1901).

Holotype, Stenocephalemys albocaudata (Ethiopian white-tailed narrow-headed rat)

Carnegie Museum of Natural History, CM 3415

Photo: John R. Wible

Colobus guereza guereza (Mantled Guereza)

American Society of Mammalogists, Mammal Image Library

Photo: P. Perry

Kobus ellipsiprymnus (Waterbuk)

American Society of Mammalogists, Mammal Image Library

Photo: P. Perry

Elephantulus rufescens (Rufous Elephant Shrew)

American Society of Mammalogists, Mammal Image Library

Photo: G. B. Rathbun

Chlorocebus pygerythrus (Vervet Monkey)

American Society of Mammalogists, Mammal Image Library

Photo: H. F. P. Payne

Camels crossing a river, c. 1911–12

Ruthven Deane Collection, Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-115846

Lepus capensis (Cape Hare)

American Society of Mammalogists, Mammal Image Library

Photo: B. D. Patterson

East shore of Lake Rudolf, near southern end

From Herbert Friedmann, Birds Collected by the Childs Frick Expedition to Ethiopia and Kenya Colony: Part 2. Passeres, Bulletin 153 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, United States National Museum, 1937).

Photo: A. B. Fuller

Syncerus caffer (African Buffalo)

Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Hall of African Wildlife

Photo: Carnegie Museum of Natural History

Diceros bicornis (Black Rhinoceros)

American Society of Mammalogists, Mammal Image Library

Photo: S. J. Bleiweiss

Paraxerus ochraceus (Ochre Bush Squirrel)

American Society of Mammalogists, Mammal Image Library

Photo: B. A. Roberts

Hippopotamus amphibius kiboko (Hippopotamus) skull

Carnegie Museum of Natural History, CM 2033

Photo: John R. Wible

Mr. and Mrs. McMillan

From B. H. Jessen, W. N. McMillan’s Expeditions and Big Game Hunting in Southern Sudan, Abyssinia & East Africa (Marchant Singer & Co., London, 1906).

Aepyceros melampus suara (Impala)

American Society of Mammalogists, Mammal Image Library

Photo: D. C. Gordon

Street scene, Nairobi, between c. 1900 and 1923

Frank and Frances Carpenter Collection, Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-92781

Preparation of Giraffa camelopardalis tippelskirchi (Giraffe), CM 2112

Photographer unknown, Untitled. 1911. Black-and-white print. Institutional Photographs. Section of Mammals. Carnegie Museum of Natural History Archives.

Ghary car

From Peter MacQueen, In Wildest Africa: The Record of a Hunting and Exploration trip through Uganda, Victoria Nyanza, the Kilimanjaro Region and British East Africa… (L. C. Page & Co., Boston, 1909).

Photo: Peter Dutkewich

Clayton, Frick Art & Historical Center, Pittsburgh, 2012

Clayton (home of Henry Clay Frick), Frick Art & Historical Center, 7227 Reynolds Street, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA. by Daderot is licensed under CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication

Portrait of Childs Frick by The Falk Studio, 1901

Courtesy of The Frick Collection/Frick Art Reference Library Archives, New York

Childs Frick with Mountain Nyala, c. 1911–12

Courtesy of The Frick Collection/Frick Art Reference Library Archives, New York

Edgar A. Mearns, between 1890 and 1910

Ruthven Deane Collection, Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-115922

Photographer unknown

My tents. Camp at Fern Spring, near Baker's Butte, Mogollon Mountains, Arizona, 1887

Mearns Collection, Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-105870

Photo: Edgar A. Mearns (1856-1916)

Mearnsia picina (Philippine Spinetail), named in Mearns’ honor in 1911

From Proceedings of the scientific meetings of the Zoological Society of London, Part III, 1878 openlibrary.org

Safari on the march

From Abel Chapman, On Safari: Big-Game Hunting in British East Africa, with Studies in Bird-Life (Edward Arnold, London, 1908).

Photo: R. J. Cuninghame

Ad for Newland, Tarlton & Co.

From H. F. Ward and J. W. Milligan, Handbook of British East Africa (The Caston [B.E.A.] Printing & Publishing Co., Ltd., Nairobi, 1912).

Equipment list

From Percy C. Madeira, Hunting in British East Africa (J. B. Lippincott Company, Philadelphia and London, 1909).

Ad for Burberrys

From C. H. Stigand, The Game of British East Africa (Horace Cox, Windsor House, London, 1909).

Ad for Wilkinson Sword Co., Ltd.

From H. F. Ward and J. W. Milligan, Handbook of British East Africa (The Caston [B.E.A.] Printing & Publishing Co., Ltd., Nairobi, 1912).

Ad for Humphreys & Crook

From H. F. Ward and J. W. Milligan, Handbook of British East Africa (The Caston [B.E.A.] Printing & Publishing Co., Ltd., Nairobi, 1912).

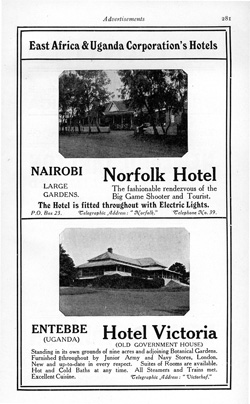

Ad for East Africa & Uganda Corporation's Hotels

From H. F. Ward and J. W. Milligan, Handbook of British East Africa (The Caston [B.E.A.] Printing & Publishing Co., Ltd., Nairobi, 1912).

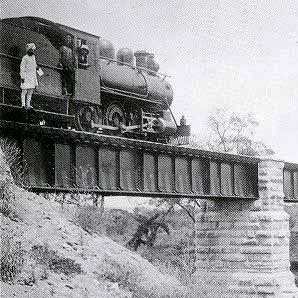

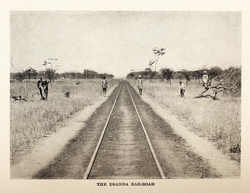

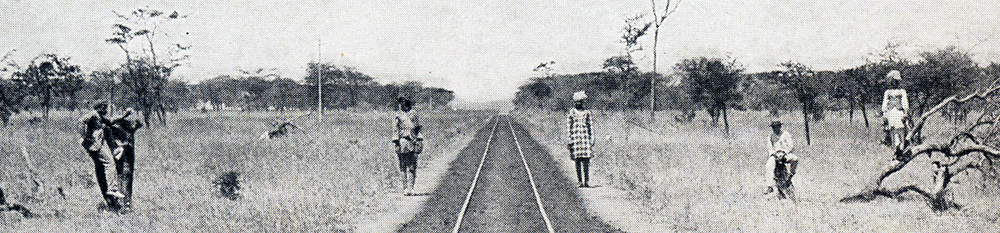

Uganda Railway

From Percy C. Madeira, Hunting in British East Africa (J. B. Lippincott Company, Philadelphia and London, 1909).

Photo: Newland, Tarlton & Co.

Baldwin locomotive enroute from Mombasa to Nairobi

From Percy C. Madeira, Hunting in British East Africa (J. B. Lippincott Company, Philadelphia and London, 1909).

Photo: Percy C. Madeira

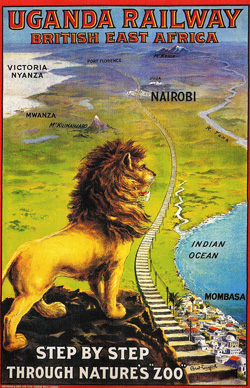

Uganda Railway poster, 1908

Courtesy of transpress New Zealand (www.transpressnz.com)

Ad for Uganda Railway

From H. F. Ward and J. W. Milligan, Handbook of British East Africa (The Caston [B.E.A.] Printing & Publishing Co., Ltd., Nairobi, 1912).

Ad for Uganda Railway

Replica Uganda Railway poster on tha Twshane Express historic steam train operated by Friends of the Rail in Pretoria, South Africa by NJR ZA is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Uganda Railway map, 1910

Courtesy of Benitz Family (benitz.com)

Crossing the Tsavo Bridge

Courtesy of Harjinder Singh Kanwal (www.sikh-heritage.co.uk)

Near Mombasa, c. 1899

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kurve_bei_Mombasa.jpg

Equus quagga (Plains Zebra)

Maasai Mara National Reserve, Kenya, 2012

Photo: Coke Smith (www.cokesmithphototravel.com)

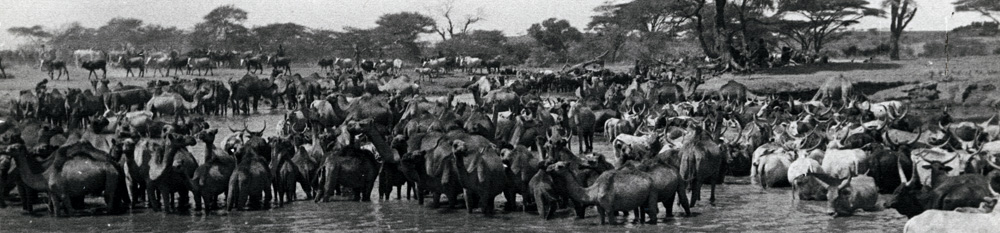

Watering hole on Frick expedition, c. 1911–12

Courtesy of The Frick Collection/Frick Art Reference Library Archives, New York

Books from Frick’s personal library

Photo: Lisa Miriello

The old fort on the main street of Mombasa, c. 1907

From Percy C. Madeira, Hunting in British East Africa (J. B. Lippincott Company, Philadelphia and London, 1909).

Photo: Percy C. Madeira

Author with reflex camera equipped with telephoto lens

From A. Radclyffe Dugmore, Camera Adventures in the African Wilds (Doubleday, Page & Company, New York, 1910).